How contested is EU integration really?

Published:

One of the truisms of EU integration theory is that the EU’s expansion into integration of extremely salient policy areas, so-called “core state powers” like fiscal and migration policy, is more likely to be met with public contestation than comparatively “boring” harmonization of rules and regulations. However, my most recent paper paper “Constraining dissensus and permissive consensus”, which was recently published in the journal West European Politics (read an ungated version of the paper here) is the first paper to empirically test and challenge this proposition.

I find, in contrast to the previous literature, that there is no automatic relationship between a policy area’s status as a core state power and it being more strongly contested than an instance of regulatory integration, digital single market policies. Instead, I find that for instance support for common defense policies is greater than for the digital single market. This is despite the former being at the very core of what it means to be a state. We also see that the relative difference between support for digital single market policies and support for a common migration policy is statistically indistinguishable from zero. This is particularly revealing, because the way that migration is a hot-button issue in domestic politics suggests that this is where we would be particularly likely to find greater opposition to EU integration.

Same story where we would least expect it

We would also expect to find that those with a strongly national identity would be equally likely to oppose all forms of core state power integration. The reason is that such identities are associated with a greater concern for national sovereignty, which would make them more likely to see all EU integration of these very important policy areas as problematic. However, this is not the case.

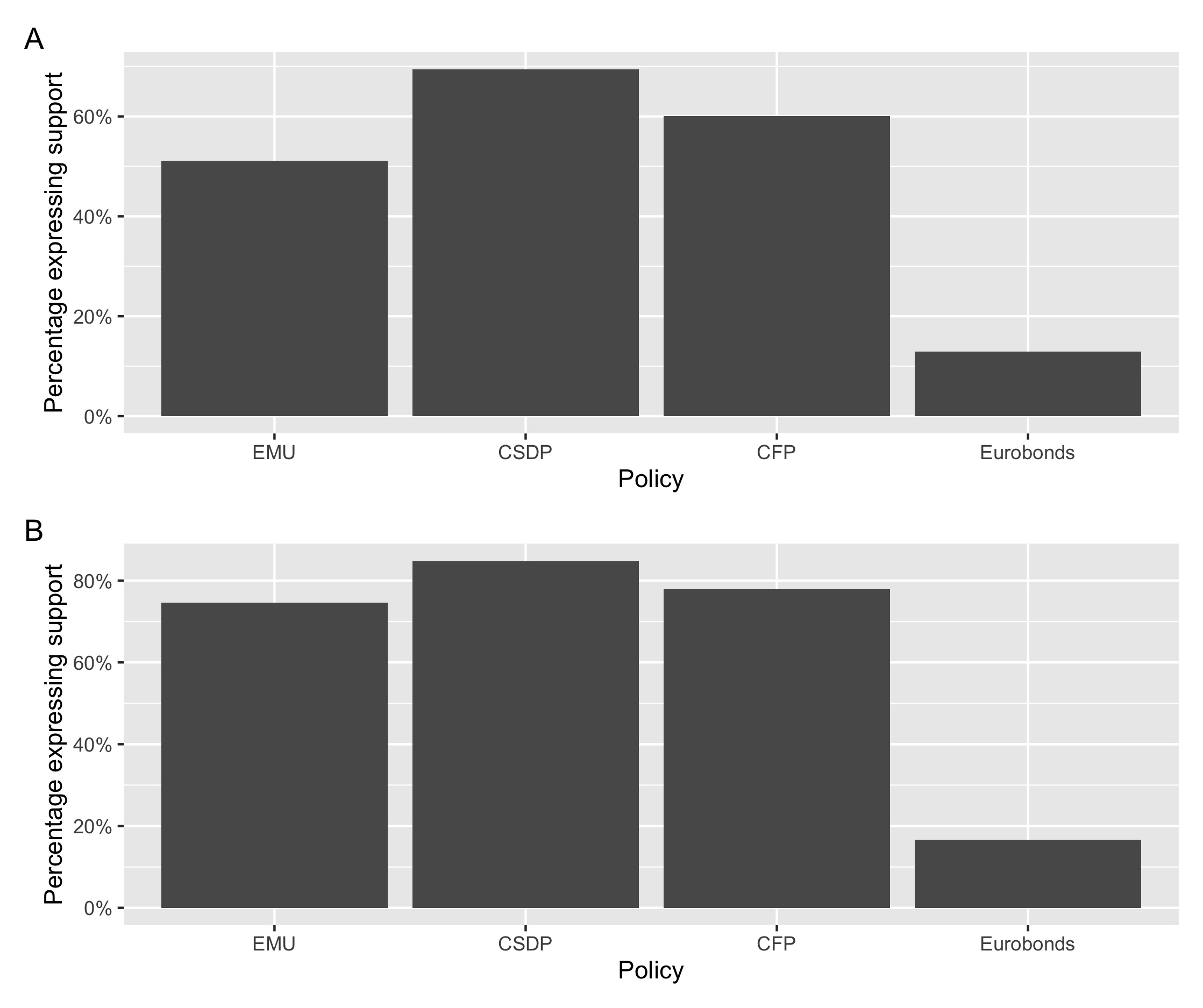

Instead (as we can see from panel A in the picture), there is a much greater support for common foreign and defence policy among exclusive nationals than for the euro and common sovereign debt. This suggests that even in a group where we would expect highly uniform attitudes towards integration, strong ambivalence exists.

What does it all mean

An important question for future research is whether this leads to support for more differentiated integration in some areas when compared to others. While my results show that some policies are more strongly supported than others, we still know little about whether this means that citizens want a differentiated EU in these areas, in which some member states participate while others do not. Secondly, we know too little about what drives this ambivalent support, and why identity seems to correlate so much more strongly with opposition to domestically, rather than externally, oriented integration. This must be the subject of further research.